The four legs of religion.

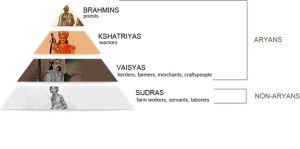

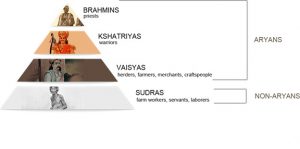

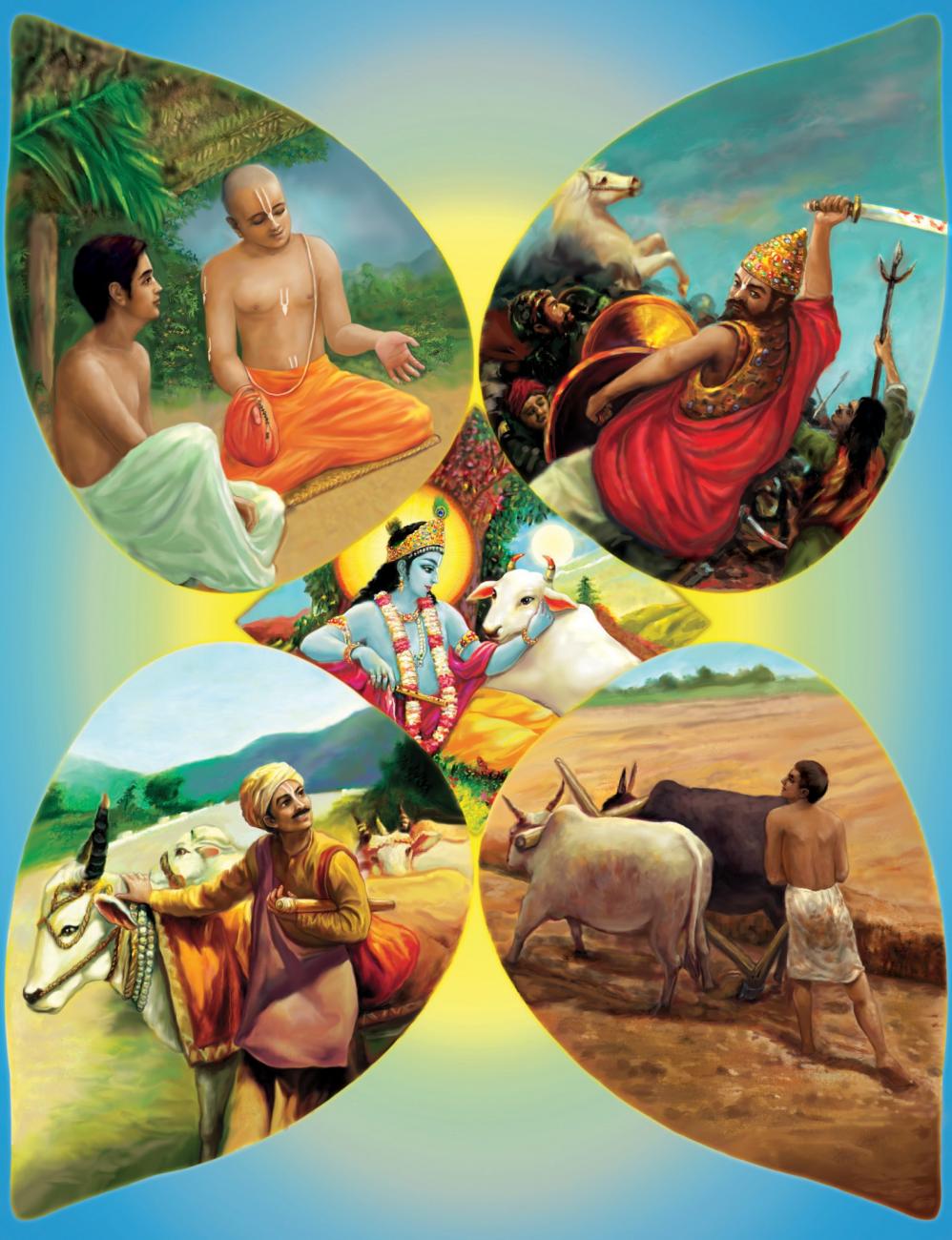

“In the beginning, during Satya-yuga, the age of truth, religion is present with all four of its legs intact and is carefully maintained by the people of that age. These four legs of powerful religion are truthfulness, mercy, austerity and charity. Actual charity, here referred to as dānam, is to award fearlessness and freedom to others, not to give them some material means of temporary pleasure or relief. Any material “charitable” arrangement will inevitably be crushed by the onward march of time. Thus only realization of one’s eternal existence beyond the reach of time can make one fearless, and only freedom from material desire constitutes real freedom, for it enables one to escape the bondage of the laws of nature. Therefore real charity is to help people revive their eternal, spiritual consciousness. In the First Canto of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, the fourth leg of religion is listed as cleanliness. According to Śrīla Viśvanātha Cakravartī Ṭhākura, this is an alternative definition of the word dānam in the present context. The people of Satya-yuga are for the most part self-satisfied, merciful, friendly to all, peaceful, sober and tolerant. They take their pleasure from within, see all things equally and always endeavor diligently for spiritual perfection. In Tretā-yuga each leg of religion is gradually reduced by one quarter by the influence of the four pillars of irreligion — lying, violence, dissatisfaction and quarrel. By falsity truth is diminished, by violence mercy is diminished, by dissatisfaction austerity is diminished, and by quarrel charity and cleanliness are diminished. In the Tretā age people are devoted to ritual performances and severe austerities. They are not excessively violent or very lusty after sensual pleasure. Their interest lies primarily in religiosity, economic development and regulated sense gratification, and they achieve prosperity by following the prescriptions of the three Vedas. Although in this age society evolves into four separate classes, O King, most people are brāhmaṇas. In Dvāpara-yuga the religious qualities of austerity, truth, mercy and charity are reduced to one half by their irreligious counterparts. In the Dvāpara age people are interested in glory and are very noble. They devote themselves to the study of the Vedas, possess great opulence, support large families and enjoy life with vigor. Of the four classes, the kṣatriyas and brāhmaṇas are most numerous. In the Age of Kali only one fourth of the religious principles remains. That last remnant will continuously be decreased by the ever-increasing principles of irreligion and will finally be destroyed. In the Kali age people tend to be greedy, ill-behaved and merciless, and they fight one another without good reason. Unfortunate and obsessed with material desires, the people of Kali-yuga are almost all śūdras and barbarians.

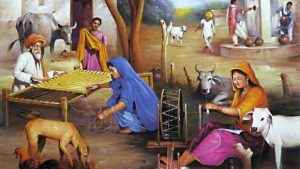

In this age, we can already observe that most people are laborers, clerks, fishermen, artisans or other kinds of workers within the śūdra category. Enlightened devotees of God and noble political leaders are extremely scarce, and even independent businessmen and farmers are a vanishing breed as huge business conglomerates increasingly convert them into subservient employees. Vast regions of the earth are already populated by barbarians and semibarbarous peoples, making the entire situation dangerous and bleak. The Kṛṣṇa consciousness movement is empowered to rectify the current dismal state of affairs. It is the only hope for the ghastly age called Kali-yuga.”

Source: A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada (2014 edition), “Srimad Bhagavatam”, Twelth Canto, Chapter 03 – Text 18 to 25.